My structural thinkinga journey into how I do design

The good and the bad thing about Design is that it is a deep subject, so deep and vast, we frequently drown in its startling world. But that drowning, that immersion can be misleading – we start seeing design as more significant than it actually is.

In 2013 I was in Berlin trying to find the Bauhaus Museum; I looked at the map and arrived at the location but couldn't really find it. I started asking random people on the street, "do you know where the Bauhaus museum is?" none of them knew where the museum was or what Bauhaus is. As a recently-graduated design student, that was shocking – "How could a German not know about the most important school of design?". I was drowning and blind. It took time to realize, but that episode taught me a few lessons:

¹ Learning to Design is learning to see.

¹ Learning to Design is learning to see.- If I wanted to apply my skills to help other people, I should step out of the design circle and be more present in the everyday world.

- Our school references is just a snip (unfortunately very white) of what we could define as Design.

- The world is so big and plural that Design (and I) are part of a whole and can't do much alone.

Years later, with those lessons, I could shape my way of seeing design¹ as Yanagi Sōetsu describes a non-dualistic form: no right vs. wrong, nor beauty vs. ugliness, nor good vs. bad. When you simplify in two realms, you lose the ability to see all the implications around and beyond it. You get blind to the whole.

My state of mind is trying to stand in and out of the circle.

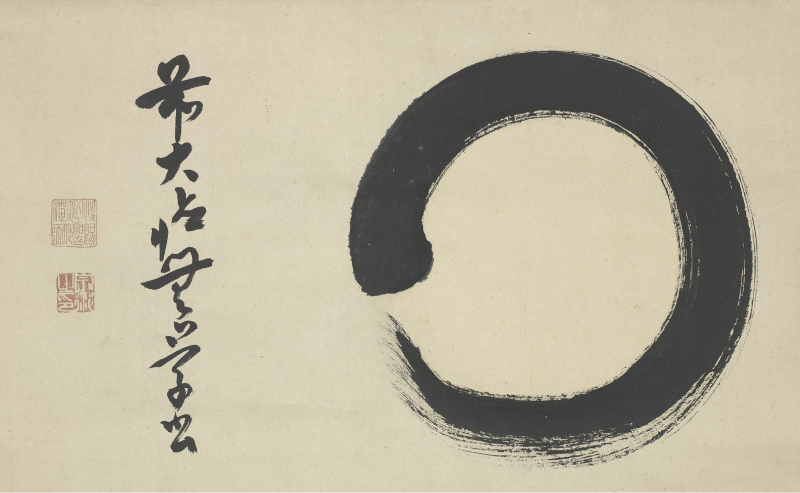

² Ensō is a circle that is hand-drawn in one or two uninhibited brushstrokes to express a moment when the mind is free to let the body create.

² Ensō is a circle that is hand-drawn in one or two uninhibited brushstrokes to express a moment when the mind is free to let the body create.The great Chinese Zen monk Kuei-shan, sought to explain the meaning of everything by making use of a circle as a symbol². One day, while engaged in training his disciples, he drew a circle on the ground, saying: "If you step into this circle, I will strike you. If you stand outside it. I will strike you just the same. "What are you going to do?" By this seeming paradox, the monk hoped to show that so long as a man persists in the dualistic realm of 'in' and 'out', he cannot possibly attain Buddhahood.

Computational Design

The Design field has many ramifications: fashion, industrial, motion, illustration, graphic, typography… they all share the same principles and, in general, have a similar timeline. Each ramification has its specificities. But for all of them, computers changed how we are thinking and delivering. Think about typography: in the old days letters were sculpted in metal and now have to be drawn with vectors and hitting pixels. To be a designer in 2020, specifically a digital designer, we should look beyond pixels. We need to understand how to speak machine. Not code, but engage in how to think computationally.

Computational thinking plays a big role in how I perceive Design. The balance of these two different realms: design searching simplicity and computers answering complexity is the most powerful combination of our times. And this becomes the additional skill that I need to force me to step out of the circle. We are translating our physical world into digital information, and once the information has a virtual representation, you can bend, combine, and transform in multiple ways.

We should focus on understanding computation. Because when we combine Design with computation, a kind of magic results; when we combine business with computation, great financial opportunities can emerge.

— John Maeda

State of mind

The design field has a vast literature about how to solve problems. My goal here is not to create or describe a new method. This is a personal record about how my mind functions while I’m doing design. It is the synthesis from what I observe, read, and learn with others. Every design problem, every project I'm being evolved in the last years runs through three states of mind:

- Frame: understand the goal and the circumstances;

- Translate: render what was framed into the design language available;

- Decision: look critically and choose the option that answers what was framed before.

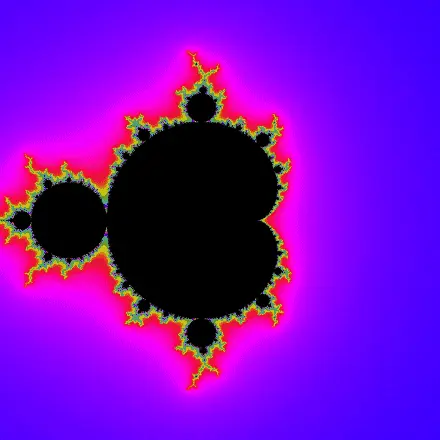

³ The Mandelbrot set named it in tribute to the mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot, a pioneer of fractal geometry

³ The Mandelbrot set named it in tribute to the mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot, a pioneer of fractal geometryThink of it as a fractal³ — it works for a feature, for a new product, or an ongoing one. It's a cycle that repeats itself infinite times until it finds the best option under the circumstances. For computational thinkers: It's a recursive loop with a state of previous interactions.

"Design isn't a march toward something known. Design is an exploration of what feels right, making iteration an essential foundation of our discipline."

— Ehsan Noursalehi

Frame

Sounds easy when you say: "start framing the problem". But in real life, it's more common than not to get distracted and lost about what you should focus on: to discover what's the most important thing to solve. The world has a lot of noise; we need to train ourselves to silence it and identify what is essential. If we don't, we run in circles or spend time in the wrong part of the problem. Always ask: What is the most important thing to solve?

In this state, I allow myself to use anything as input material. User and stakeholder interviews, mental models, walking, informal conversations, benchmarking, social media research. Anything that can help frame the problem from different perspectives and find new connections. I like to write everything down to clear my mind and extract the essence. What's the most important thing to solve?

Translate

My short answer for the classic "what doing design looks like?" question is: Translate abstract thinking into practical things. When you talk about branding, you need to translate concepts: innovation, boldness, tradition, respect to shapes, colors, typography, space, contrast, proportion, harmony, rhythm, tone of voice... It is hard because the translation is not just for you, it's for others to understand and these concepts are extremely subjective, so you always have to compromise.. For digital designers, we have the advantage that our branding colleagues have more vocabulary to help us translate (interactions, time, space, movement...)

At this state, is the time we translate everything we have framed: all the abstract concepts and ideas in our heads – and draw on the screen. It is not something that we achieve in the first attempt; it is wearying and laborious. Any judgment or critical thinking should be postponed. It's time to explore and stress ideas. The goal is to translate with the minimum amount of loss, like any file format that goes from zeros and ones to pixels on the screen. Every time I get stuck or thinking, I'm far from what was framed. Then I remember what Paul Rand defines as Design: "Design is relationships. Design is a relationship between form and content." and go back to the canvas.

Decision

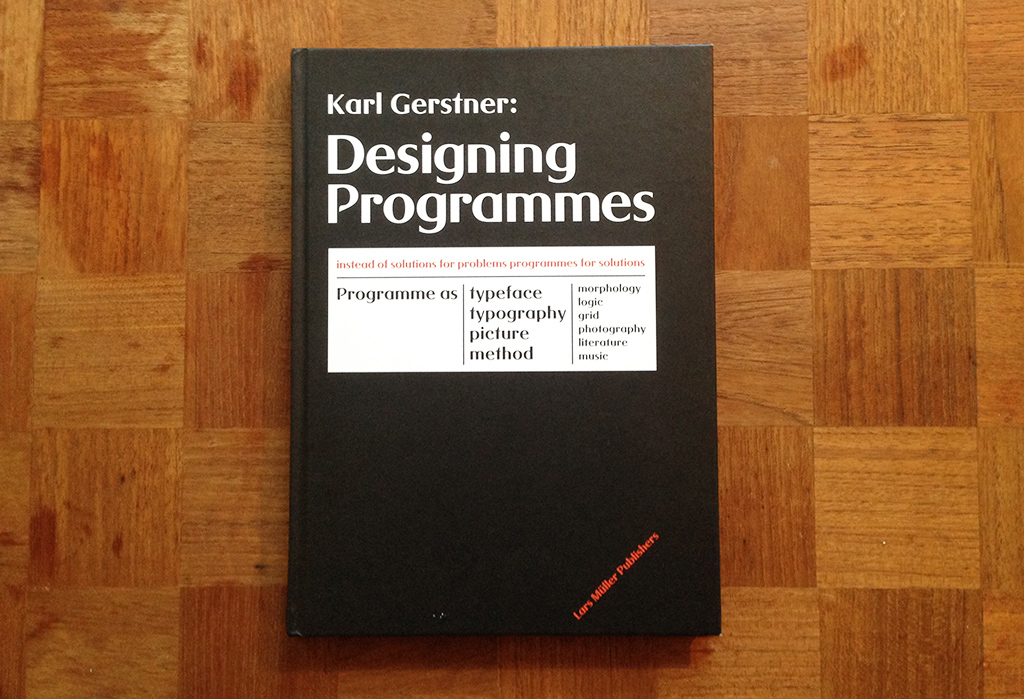

The third state is where the mind shifts to a critical mode. Leave the ego and the pet ideas behind, shut down the distraction from the outside world, and truly look for what was translated. What is working? Is it aligned to the goal? If you are the person who will use it, what do you feel? What is not good enough? Should we reframe the problem? As Karl Gerstner wrote: "There is always a group of solutions, one of which is the best under certain conditions."⁴

⁴ Karl Gerstner theorize the systematic thinking before the computers

⁴ Karl Gerstner theorize the systematic thinking before the computersIn my personal view, this is the most difficult part of the process. When machines do Design, they can't do this part. A computer can generate thousands of translations but can't decide what the option they should pick for the next iteration. The computer can't judge beyond numeric parameters: the social impact of a feature, the ethics behind it... That's why the human eye is needed for this decision. We design the unknown; in the table, we only have hypotheses, so my way to go is to show earlier, get feedback, and listen to others. It is a way to get help, look critically at work, and make responsible decisions. Don't forget we design for the other, not for ourselves.

What I stand for

"Work for life and not for palaces, temples, cemeteries, and museums. Work in the midst of everyone, for everyone, and with everyone."

— Aleksandr Rodchenko 1921

Work in the tech industry relies upon us, designers, developers, product managers, a grand task of addressing the imbalanced society. I have the privilege to stand for my beliefs in my career, and now, more than ever it is important to take responsibility for our work's impact. I will fight and work hard for privacy, diversity, creativity, and empowerment to enhance humans through computers.

I'm on a journey to become a better person than I was yesterday. Learning with other cultures, respecting every person, and listening to what people have to say is my way of making computational environments more human.

Thanks Bernardo Lemgruber, Fernanda Woijick, Fabricio Texeira and Renata Schwegler for your thoughts and feedback.

Did you like it? Subscribe to receive updates on my way of thinking: